Food Defense

DEFINITIONS FOR FOOD DEFENSE AND RELATED TERMS

Some working definitions are appropriate to frame the discussions in this article. As a relatively new area of focus within governments and food producers, the terms used to describe protections from intentional contamination are evolving. The language may change further as global partners continue to collaborate.

Food Safety

Food safety has its focus on reducing the risk of unintentional contamination in the food supply, be it natural, accidental, a result of negligence or violation of food safety principles due to technical ignorance. Food safety is a well-established area of effort that has been around for decades. Universities worldwide have well-regarded food safety programs. Most governments have agencies dedicated to food safety. Producers increasingly have food safety management programs based on global standards. Cold-chain practices, risk analysis methods such as operation risk method (ORM) and hazard analysis critical control point (HACCP) are well understood (and highlighted prominently in reference materials such as this one). Food safety frequently focuses on a relatively short list of well-studied pathogens, suchas pathogenic strains of Listeria, E. coli and Salmonella, along with chemical contaminants

and physical hazards like wood or metal fragments. Some of these contaminants are inherently found in the environment or production systems. Inspection and detection methodsexist for these agents. Many food processing systems include treatments (oxidizing or heat treatments) or compositions (low water activity, pH) that inactivate pathogens.

Key points: Accidental contamination, well-established best practices, known agents.

[ BRSM Certification is accredited for QMS ISO 9001, EMS ISO 14001, OSHMS ISO 45001, FSMS ISO 22000 and QMSMDD ISO 13485 and … ]

Food Security

Food security has its focus on the availability of nutrition for a population. Despite the large-scale agriculture, industrial food manufacturing and global distribution of the global food supply, there is still a great deal of hunger in the world. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates “that a total of 925 million people are undernourished in 2010” with “developing countries account[ing] for 98 percent of the world’s undernourished people.” Many populations (nations, regions or people) have an insufficient supply of food, and they are “Food Insecure.” Populations with sufficient supplies of food have “Food Security.” This problem is projected to increase due to population growth, climate change and related factors (FAO, 2010). Note: Some documents may use the term food security to describe measures to reduce the risk of intentional contamination. If you are unsure, you should try to clarify the local context of the term.

Key points: Sufficient food for a population.

Food Defense

Food defense has its focus on the prevention of the intentional contamination of the food supply. Many agents can be used for intentional contamination. In addition to the agents normally identified with food safety, these can include other chemical, biological, physical or even radiological agents. Many potential agents are highly toxic and are not prevented or inactivated by conventional food safety interventions. Most of these potential agents are difficult to detect, or at least difficult to detect when in a variety of foods. The motivations for intentional contamination can be as varied as the agents. They can range from local grievances to economic advantage to political disruption to mass casualties. The capabilities of perpetrating an intentional contamination also have a broad range, from the limited effort of an individual to the significant capabilities of a well-organized international terrorist cell.

Key points: Intentional contamination, unknown agents, limited detection methods, motivations and capabilities vary with the perpetrator.

[ BRSM Certification is accredited for QMS ISO 9001, EMS ISO 14001, OSHMS ISO 45001, FSMS ISO 22000 and QMSMDD ISO 13485 and … ]

Food Protection

Food protection is an “umbrella term” to encompass both food safety and food defense activities. This pays homage to the fact that it is often the food safety professionals that become responsible for food defense. This reflects various similarities and overlaps in the work of food safety and food defense. For example, both food safety and food defense benefit from control and inspection of incoming materials and from a robust recall and recovery program. Note that in terms of regulatory authorities there are different organizations involved, e.g. food control agencies for food safety versus police or homeland security agencies for intentional contamination. Note: There are also several fundamental differences between food safety and food defense because of the intentional element. Malicious intent and intelligent adversaries must be considered in food defense. A change in thinking is required when food safety professionals also manage food defense measures. They must begin to “think like the bad guy.”

Key points: Emphasizes the similarities with food safety, may diminish the differences.

Bio-terrorism, Agro-terrorism and Bio-defense

Bio-terrorism, agro-terrorism and bio-defense focus on biological attacks of several kinds. These can be attacks against crops or livestock as well as the food we eat. The inclusion of the word “terrorism” describes crimes that are politically motivated. Food defense is concerned with intentional contamination of food that is politically motivated and motivations that are economic or revenge based. While intentional attacks against the food we eat or the feed stocks that make our food may be considered bio-terrorism or agro-terrorism, those terms are more often used in the contexts of crops and livestock, or as an umbrella term for all biological-based terrorist attacks against food.

Key points: Attacks against any food, crop or livestock rather than a focus on the food we eat.

FARM TO FORK

Food defense borrows the notion from traditional food safety and cold chain to treat the entire food supply as an integrated system. The weakest link between the farm and the consumer may be the place where an intentional contamination occurs. You may also hear comparable terms such as “farm to table,” or in Australia, “paddock to plate.” With food defense two factors make protecting the entire supply chain even more critical than with food safety. The first factor is the malicious intent of the perpetrator. If they have studied the food system, they may choose to attack at the location with the fewest defenses, the location where they can do the most harm. Some vulnerability assessment methods, in fact, focus on how a perpetrator would choose a target. The second factor is the difficulty of inactivating some agents that might be used in an intentional attack. Traditional food safety protocols heavily emphasize sanitation conditions at food producers and the critical control points (CCPs) of “kill steps” like pasteurization to reduce the risk of a food safety incident. These measures would be totally ineffective against many potential contamination agents.

Note: Several food safety incidents have illustrated the weakness of relying too heavily on the controls at the food producer. The E. coli outbreak in leafy greens in the United States in 2006 caused a significant health impact despite controls at the producer. Significant improvements in good agricultural practices (GAP) were instituted as a result (CDC, 2006). Most food producers are not vertically integrated to the extent that they can control the entire food supply from “farm to fork.” They must instead influence the defensive ability of the supply chain that is outside their control in another way. To do this they borrow techniques from traceability methods, looking one step ahead and especially one step behind as part of supply chain verification.

[ BRSM Certification is accredited for QMS ISO 9001, EMS ISO 14001, OSHMS ISO 45001, FSMS ISO 22000 and QMSMDD ISO 13485 and … ]

TYPES OF RISK AND HAZARDS

In traditional food safety we look at the various mechanisms (vectors) that could create a food safety incident. In food defense, when we talk about the types of risks and hazards we can consider the various types of perpetrators that might commit an intentional contamination. What kinds of people or groups are they? What are their motivations? What are their capabilities? Are there targeted mitigations for those specific perpetrators?

We can also consider the various agents that might be used. Taken in combination, these represent the threat vectors we need to guard against. The good news is that much of what we do to protect our processes from one potential perpetrator will also protect us from others. The bad news is that this is not entirely true, because their capabilities are different. Consider perimeter fences that will help keep out competitors or local political threats, but would do little to slow down an insider or a well-organized terrorist cell.

Perpetrators: Motivations, Capabilities and Targeted Mitigations

Owners and Managers; Economically Motivated Adulteration (EMA)

While we might first think of intentional contamination with respect to criminal or terrorist activity, often with a political motive, perhaps the most pervasive form of intentional contamination is to improve profits: economically motivated adulteration. Economically motivated adulteration can take the form of diluting a product, substituting inferior ingredients or adulterating with potentially hazardous ingredients that might improve the apparent value (with the intention of “fooling” the current quality assurance of analytical methods used to establish value). Fake products (imitations/counterfeits) are another form of economically motivated adulteration. A challenging factor with economically motivated adulteration is the nature of the perpetrator – the owner or key management staff. They have ready access to all systems. They understand the process thoroughly and have the means to circumvent any physical security measures. Their workforce may be unaware of, unable or unwilling to report, their suspicious activities. There is another interesting conundrum when considering the potential health impacts of economically motivated adulteration. The owner/perpetrator presumably does not desire people to become ill; their motivation is economic gain not human harm or political impact. So they may dilute or substitute with a material of less nutritional value though not necessarily one that is pathogenic. On the other hand, because the adulteration is more likely to go undetected for some time, the cumulative health impact could be quite great. As an example, in 2008, about 300,000 children in China became ill and at least six babies died when the milk used for infant formula manufacturing was adulterated with melamine (The New York Times, 2011). In 2004, about 50 children died from fake infant formula, which provided little or no nutrition (Watts, 2004).

[ BRSM Certification is accredited for QMS ISO 9001, EMS ISO 14001, OSHMS ISO 45001, FSMS ISO 22000 and QMSMDD ISO 13485 and … ]

Special capabilities: To disguise the substitution of one ingredient for another, using the excuse of controlling proprietary information to hide the actual formulation from employees.

Limitations: The selection of agents is limited to adulterants the owner or manager believes will get around QA systems, and those that will be benign, so as to allow the adulteration to be perpetuated over time for the greatest economic gain.

Targeted mitigations: EMA agent informed analysis by the customer.

Employees and Other Insiders

A “disgruntled employee,” angry with a supervisor or co-worker, may be one of the most difficult threats to guard against. This person may have access to many areas within the facility, may know the best places to contaminate without being caught and may not raise any suspicion even when away from their normal work area. The nature of the design and operation of many food manufacturing facilities allows almost any employee to be in almost any work area. Even new or temporary service employees often have relatively unrestricted access. Color-coded hats or uniforms are often used to designate job function, like supervision or quality, and not what area the employee

should be working in. When considering employees, also consider other people who have regular access to

your facility: vendors, contractors, sanitation personnel and other temporary support employees can have similar access and motivations. Many of the physical security measures we might first think of when considering food

defense, like fences and guards, are powerless against an inside threat. Even cameras might be ineffective in stopping an insider if they know they are not being monitored in real time. Enhancements of our physical security measures and additional behavioral measures are needed. The motivation of an insider threat may be retribution for some harm or slight. As such, the goal is to do harm to the owner or company, not necessarily to create a large health impact. So the contamination may be one that becomes obvious, changing the color or composition of the product in a way that is detected before the product would make it to the consumer. There is one exception: the special case where the insider belongs to, or has been compromised by, a terrorist group that does seek to do harm.

Special capabilities: To freely bypass external security measures, and in many cases have access to food mixing operations that make a good place to introduce a contaminant.

Limitations: The agents available to employees are limited. They usually would not have access to highly toxic agents in high concentrations.

Targeted mitigations: Zoned internal security measures, “buddy” systems, surveillance. Background security screening of all personnel, not only full-time employees, but also vendor and temporary support personnel.

Competitors

Like a disgruntled employee, a competitor may wish to harm another company. A competitor likely does not have access to the facility (though this could happen in some cases of prior employment). The competitor would, however, have significant knowledge of the processes and possibly the vulnerabilities.

Special capabilities: To understand the most effective place to contaminate and recognize those processes in another operation.

Limitations: The agents available to competitors could be limited. Access may be limited as it is to other outsiders. There may be restraint on the part of a competitor if they understand that any public awareness of tainted product could damage the entire market including their own business.

Targeted mitigations: Prompt removal of access privileges for all previous employees. Industry education regarding the shared impact of a contamination event.

Local Extremists

Because the threats of local extremists are politically motivated, they can be termed terrorists. They are listed in this article separately from global terrorists because the capabilities of these local terrorists may be much different. (In some food defense programs, all terrorists, local and global, are considered as a single category of threat – National Standard of the People’s Republic of China, 2010.) What sets extremists apart from the previously classified groups is their willingness to cause harm to people. While they may attempt to achieve their goals through economic

harm and publicity, they may prefer to make their statement by impacting public health. There have been several intentional food contamination events by local extremists. Fortunately they have been fairly limited in scope. These events have generally been targeted at the “last mile” such as retail food establishments. As an example, in 1984 in The Dalles, Oregon, USA, members of a religious commune deliberately contaminated salad bars at 10 restaurants. A total of 751 persons were stricken with Salmonella gastroenteritis associated with eating or working at these restaurants (Torok et al., 1997). This was a test run on their ability to impact voter turnout at a local election.

[ BRSM Certification is accredited for QMS ISO 9001, EMS ISO 14001, OSHMS ISO 45001, FSMS ISO 22000 and QMSMDD ISO 13485 and … ]

Special capabilities: To organize and conspire with others committed to a cause. They may research methods and agents in advance.

Limitations: The most esoteric methods and most toxic agents may not be available. They may be restricted only to simple access points.

Targeted mitigations: Special emphasis on retail food establishments. Facility access controls in manufacturing environments such as fences, guards and access badges. HR practices.

Global Terrorist Threat

Highly organized global terrorist attacks could target the food supply with the intention of causing significant illness and deaths. The impact could be more tragic than bombing a hotel or crashing an airplane. There is evidence that global terrorist groups have at least considered attacks on the food supply. This evidence includes captured notes from a raid on an Al-Qaeda camp (Tarnak Farms Afghanistan) in 2001 that illustrated portions of the food supply and listed potential actions (Hoffman and Kennedy, 2007). There is no confirmed evidence to date that global

terrorist groups have executed an actual attack against the food supply, although such events have aroused suspicion. What we realize, however, is the historic vulnerability of our food supply to a potential attack. The supply chain is vast, from fields, to factories, to endless distribution routes and countless consumers. It is broadly recognized as the most complex of supply chains (Food Safety Magazine, 2011). We also realize the devastating impact a significant attack could have. How many people have become sick or died in some of the major food safety incidents of the last decade, and how many more people could be harmed by a well-orchestrated attack on a food plant? How many more people could be harmed using highly toxic agents that are not inactivated

by current processes and not detected by current methods?

Special capabilities: To organize, conduct surveillance of potential targets, practice attacks and coordinate asymmetric attacks against multiple targets. They are also able to recruit or place an insider in an organization, giving them many of the capabilities previously discussed for company insiders. Potential access to any agent desired.

Limitations: The planning activities required to organize a coordinated attack make them susceptible to detection by government authorities. Surveillance or trial exercises may make them detectable by alert plant personnel.

Targeted mitigations: Collaboration with law enforcement or national security organizations and a comprehensive and layered food defense system that includes trained and alert employees or authorities.

Agents

In food safety we concentrate on a list of established agents identified as contaminants. They are naturally occurring and/or unintentionally introduced and have been reasonably well studied. The situation is much more complex in food defense. A broad range of toxic agents could be used for an intentional contamination, including biological, chemical, physical and radiological agents. Many of these agents are not well understood and we have little experience detecting them in the food supply or inactivating them. It is natural to think that we should know what agent we are guarding against, but in one respect, this really is not necessary. When we “think like the bad guy,” we look for an agent and a contamination point that is not inactivated by the normal manufacturing process. If we create a food defense plan based on some specific agent, we might overlook potential vulnerabilities based on our ability to inactivate that agent, such as points upstream of a pasteurization point. If we create a food defense plan based on the idea that the agent that will be used will cause harm and will make it through our process, we can address additional vulnerabilities. [Hint: Create your food defense plan based on an agent called “really bad stuff” that is highly toxic, difficult to detect and will not be inactivated by your process or supply chain.] After you have created an agent-agnostic plan, there are two additional benefits to going back and looking at the specific characteristics of different agents. 1. You may be able to create some additional agent-specific mitigation that further reduces your vulnerability to specific agents or types of agents. For example, a slightly higher pasteurization temperature may inactivate a broader range of biological agent as many US dairy processors have done (Detlefsen, 2005). (Remember that contamination could occur after pasteurization, so you cannot leave those downstream systems unguarded.) 2. You may improve your ability to debunk a hoax of contamination. In the event of a hoax that claims a specific contamination of your product, you are better prepared to explain to the public how that agent would be inactivated by your process, or how the quantity added would be incapable of causing mass harm. Much of the information on specific agents is either limited or classified as there is no “normal” reason to need it or provide information beneficial to potential perpetrators. Additional information and references on chemical and biological agents (Kennedy and Busta, 2007) of concern is, however, available.

Detection: Methods to detect the introduction of intentional contaminates are being studied. Today there are no commercially available broad-spectrum test methods available.

METHODS OF VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS

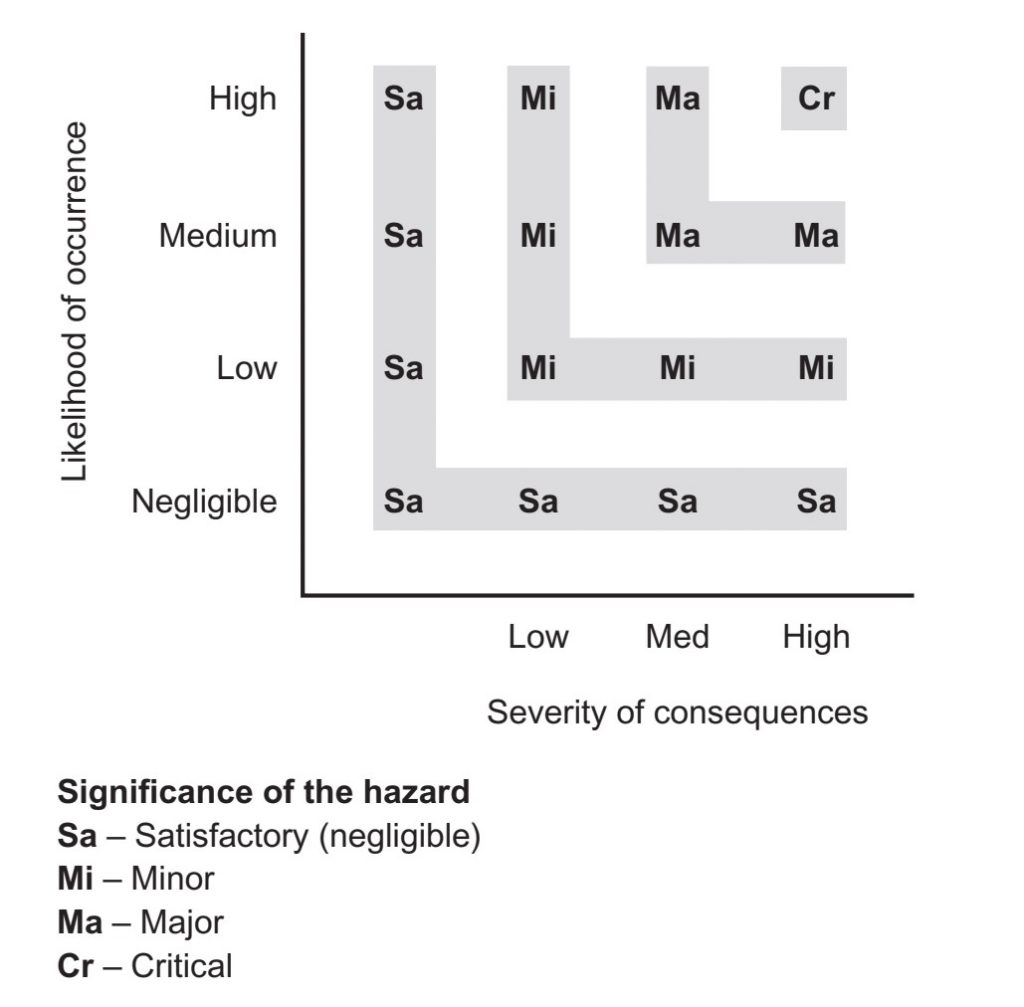

Risk analysis for food safety focuses on known hazards that do occur with reasonable probability to analyze the impact, with a goal of creating mitigation measures to reduce the impact. The focus is on controls. There are several methods to assess food safety risks, including the eye of an experienced practitioner. Hazard analysis critical control point (HACCP) is the global standard and is fundamentally based on operational risk management (ORM) principles. The ORM analysis is usually displayed as a two-dimensional health risk assessment model as displayed in Figure .1 by the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO, 1998). For food defense, the math is very different as it focuses on vulnerability assessment rather than risk assessment. An event of intentional contamination has no normal likelihood of occurrence, and an unknown potential for occurrence but the consequences could be devastatingly off the chart. For this reason the analysis is on vulnerabilities in food defense, with a goal of creating mitigation measures to take an already low likelihood of occurrence and reduce it even further. The focus is on vulnerabilities instead of controls. There are several methods to assess the vulnerabilities of a food production facility or system, including the eye of an experienced practitioner. CARVER + Shock, or a derivative of this method, is often used though there is as yet no apparent global standard.

[ BRSM Certification is accredited for QMS ISO 9001, EMS ISO 14001, OSHMS ISO 45001, FSMS ISO 22000 and QMSMDD ISO 13485 and … ]

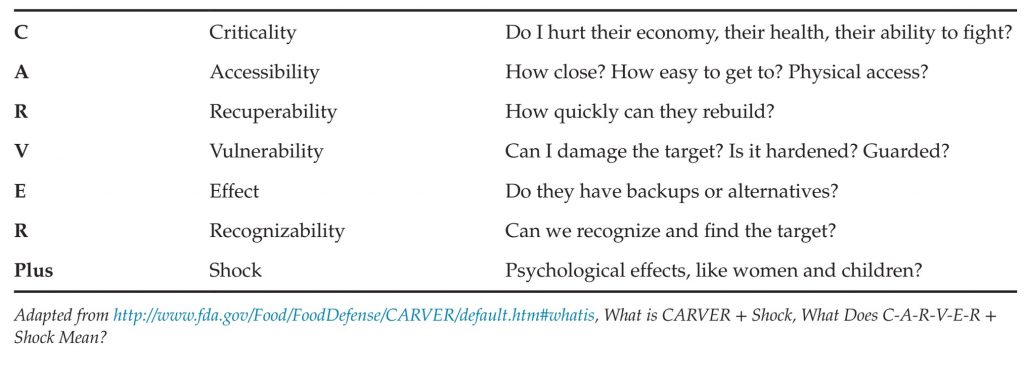

CARVER + Shock

CARVER + Shock is a seven-attribute scoring method used to assess the most vulnerable operations in the food supply chain. It can be used across supply chain elements or within an individual production facility. CARVER + Shock was adapted from a military targeting method used to select targets by giving those targets a preference score. Some targets are more hardened, others better guarded, some are easier to recognize, others easier to rebuild and some will cause more disruption. Consider the possible military targets in Figure .2 and decide how you might score them low to high against Table .1 that lists the seven CARVER + Shock attributes. When we use CARVER in the food industry, we score each unit operation (also known as process step) for each of the seven attributes. This results in a target preference score; if a “bad guy” were to target our operation, the higher scoring operations would make the most desirable targets.

FIGURE .1 Example Operational Risk Management analysis, usually displayed in a two-dimensional health risk assessment model.

devastatingly off the chart. For this reason the analysis is on vulnerabilities in food defense, with a goal of creating mitigation measures to take an already low likelihood of occurrence and reduce it even further. The focus is on vulnerabilities instead of controls. There are several methods to assess the vulnerabilities of a food production facility or system, including the eye of an experienced practitioner. CARVER + Shock, or a derivative of this method, is often used though there is as yet no apparent global standard.

CARVER + Shock

CARVER + Shock is a seven-attribute scoring method used to assess the most vulnerable operations in the food supply chain. It can be used across supply chain elements or within an individual production facility. CARVER + Shock was adapted from a military targeting method used to select targets by giving those targets a preference score. Some targets are more hardened, others better guarded, some are easier to recognize, others easier to rebuild and some will cause more disruption. Consider the possible military targets in Figure .2 and decide how you might score them low to high against Table .1 that lists the seven CARVER + Shock attributes. When we use CARVER in the food industry, we score each unit operation (also known as process step) for each of the seven attributes. This results in a target preference score; if a “bad guy” were to target our operation, the higher scoring operations would make the most desirable targets.

FIGURE .2 Examples of possible military targets that could be scored from low to high against the seven CARVER + Shock attributes listed in Table 1.

Knowing where the best targets are helps you understand where you should focus mitigation measures. Knowing why some unit operations are the most preferred targets helps you understand what mitigation measures might be most effective in making those targets less desirable. The goal of the CARVER analysis is a ranking of unit operations, not the actual score that is calculated, as a score is not transferable across a supply chain. The process steps with the highest ranking are the locations where you want to consider additional mitigation measures.

The CARVER analysis starts with a flow chart to describe the process flow within a portion of the supply chain such as your facility. A flow chart used for HACCP planning can usually be adopted for this purpose, but operations that would not be a food safety risk need to be added. Scoring tables used for a CARVER analysis are often based on a catastrophic event on a national level. The scoring can be adjusted for an individual facility. The key factor is that

the analysis helps you differentiate one unit operation from another.

Note: CARVER + Shock analysis often uses the term “nodes” for what we might call a unit operation or process step.

CARVER + Shock Software

[ BRSM Certification is accredited for QMS ISO 9001, EMS ISO 14001, OSHMS ISO 45001, FSMS ISO 22000 and QMSMDD ISO 13485 and … ]

The United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) has developed a software tool to assist in performing a CARVER + Shock analysis. It helps guide the user using an interview process, and does all the behind-the-scenes math that would be needed to score all of the unit operation (nodes).

TABLE 1 CARVER Attributes

To locate and download the free software, enter the address for US FDA Food Defense, www.fda.gov/fooddefense. Use the site SEARCH tool to search for “VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT.” The software has three main components. The first is to outline the facility using a flow diagram. The second is to respond to a series of interview questions that is generated based on the flow diagram. The final component displays the ranked scores as well as some suggested mitigation measures. [Hints (based on software for manufacturing, version 2): 1. Choose a representative operation or line. Many of the insights you gain from one analysis will be appropriate for other similar lines. 2. Keep the flow chart fairly simple. The number of interview questions is proportional to the number of chart elements. Group like operations in the same area together and score for the worst (i.e. all “blending” might be described as a single chart element). 3. Rename each chart element with a preceding numeral in order of the process flow. The interview questions are asked in “alphabetical” order of the chart element names, not in

the sequence of the process flow. 4. Choose a representative product and answer the interview questions based on that product. Many of the insights you gain from one product will be appropriate for similar products.]

Alternative Assessment Methods

Guidance Documents and Checklists

There are many guidance documents and checklists now available that suggest mitigation measures that a food production facility should consider. At the time of this writing, most of these are suggestive in nature, and not required by law. Exercising one (or several) of these checklists can identify vulnerabilities when you realize a suggested mitigation measure is not in use in your facility. While not as stringent as a CARVER + Shock analysis, these checklists can still be beneficial on their own. This is because they have been created based on the results of numerous stringent vulnerability analyses, like CARVER. Checklists are available for many industry segments and from many sources including government agencies and universities. You can search the internet for current checklists and guidance documents. There are several available from the US FDA and the United States Department of Agriculture (US DA): http://www.fda.gov/fooddefense and www. usda.gov. There is active research on new methods as well, so the tool set is evolving (Newkirk, 2010).

“Mini” CARVER + Shock

When analyzing entire industry segments and comparing one segment to another, there is some benefit in using all seven attributes in the CARVER + Shock method. Within a single organization, and certainly within a single facility, some of the attributes do not help to differentiate one unit operation from another, so they no longer add value to the analysis. As an example, if there is a major contamination event at your facility, you either do or

do not have backup manufacturing capability available (the EFFECT score). This is true regardless of what point of your operation is contaminated. So there is no benefit to you to scoring each unit operation for EFFECT; every process step would have the same score! In fact, the second version of the US FDA CARVER + Shock software puts more emphasis on only four of the scoring criteria to simplify the interviews. This had no impact

in the validity of the scores. The software scores are based primarily on CAV (Criticality, Accessibility and Vulnerability) with a little impact from R (Recuperability). Taking this one step further within a single facility, Criticality and Recuperability will usually be scored the same or very similar. Since the goal is a ranking of unit operations, not a specific numerical score, using a score based only on AV (Accessibility, Vulnerability) will

still provide a valid ranking of your most at risk operations. As an example, the exercise tools used for Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Food Defense workshops use a simple two-attribute scoring system: Accessibility and Vulnerability (Periscope Consulting, 2010–2012).

Food AG Sector Criticality Assessment Tool (FASCAT)

The National Center for Food Protection and Defense (NCFPD) at the University of Minnesota developed an assessment tool that looks across entire systems of the food and agricultural sector. It is designed for national or state agencies to evaluate their many food operations to determine which types of operations might be more critical. It helps to retain equity in cross-sector critical system identification, using attributes like overall size and

nature of distribution and the potential consequences of various threats (Hennessey, 2010; Food and Agriculture Sector-specific Plan, 2010). A practitioner evaluating an individual factory and not a supply chain will find FASCAT of limited benefit as it is a systems analysis tool. A large producer with many facilities, especially facilities of different types, may find FASCAT or future derivative tools beneficial in determining where to emphasize their food defense efforts.

MSHARPP

MSHARPP is an Air Force targeting matrix to analyze likely terrorist targets. It is being evaluated by some countries for potential use in evaluating likely food industry targets (Air Force Antiterrorism Standards, 2005).

The scoring attributes have some similarity to CARVER, with the acronym standing for Mission, Symbolism, History, Accessibility, Recognizability, Population and Proximity.

[ BRSM Certification is accredited for QMS ISO 9001, EMS ISO 14001, OSHMS ISO 45001, FSMS ISO 22000 and QMSMDD ISO 13485 and … ]

The Eye of an Experienced Practitioner

After conducting numerous checklist-based assessments, workshops and CARVER + Shock analysis, there are some individuals who will have a very good “eye” for vulnerabilities and can develop a basic vulnerability assessment by walking through your operation. You might use an approach like this to get your food defense program started quickly. If you use a food defense practitioner to give you a vulnerability assessment based on a tour and discussion to get your program going, you should get all recommendations in writing. It would be then prudent to consider continuing with a more detailed and systematic assessment to assist you in refining your program over time.

PREVENTIVE MEASURES

To reduce the risk of intentional contamination, the focus for industry is on mitigation measures that reduce the vulnerability of an attack (Khan et al., 2001). The focus is on prevention. You may also hear the following terms used in the context of food defense: detection, response and recovery. These are the focus of government agencies and in some cases universities. Detection may be used to describe the detection of an intended attack or detection methods used to detect arcane contaminants within our foods. Response describes the laboratory capacity and information sharing as well as the regulatory and law enforcement work needed after a contamination event occurs. Recovery deals with restoring the ability of our facility or system to produce after a contamination, including the discarding of cleaning materials, decontamination of surfaces and restoration of consumer confidence. While you may want to stay abreast of what government agencies are doing in the areas of detection, response and recovery, industry can have the most impact by helping to prevent a contamination. It is mitigation measures that make it more difficult to succeed that help to prevent an attack. This section will focus on two different types of mitigation measures. First, there are basic mitigation measures that apply to nearly any food manufacturing facility. Second, there are additional targeted mitigation measures put in place after performing a vulnerability assessment (as described previously). You can think of the basic mitigation measures like the prerequisite programs you put in place for your food safety program (GMPs, sanitation, etc.). They give you a good foundation and partially reduce your risk. You can think of the targeted mitigation measures like the CCPs you put in place with an HACCP plan: they are specific to your particular vulnerabilities, and further reduce your risk. Many of the mitigation measures recommended in food defense are already in place for other reasons. For example, good traceability and recall programs support food defense needs as well as food safety needs. Traceability and recall, as important as they are in food safety (Food Safety Magazine, 2010), are even more time critical in food defense as models show how many more lives could be harmed each day following a major intentional contamination. But you may need to adjust these existing measures when you begin to “think like the bad guy.” For example, your emergency evacuation procedures may need to address preventing others from entering your facility during the evacuation, not just getting everyone out.

Comparison with HACCP

While it is helpful to make a comparison between the processes of creating a HACCP plan with the process of creating a food defense plan, the details are quite different. In food defense, the mitigations are put in place to further reduce the risk of occurrence of events of exceedingly low probability, not to reduce the impact of events of known probability. There is also some danger in thinking like an HACCP practitioner. Once you begin to rely

on some control, like pasteurization, to reduce the impact of an intentional contamination, you might overlook the small risk of occurrence of a contamination after the pasteurizer and fail to further reduce that risk with appropriate mitigation measures. Even more easily, you might overlook the small risk of contamination upstream of the pasteurizer by a heat stable compound and fail to further reduce that risk.

[ BRSM Certification is accredited for QMS ISO 9001, EMS ISO 14001, OSHMS ISO 45001, FSMS ISO 22000 and QMSMDD ISO 13485 and … ]

Basic Mitigation Measures

Basic mitigation measures generally apply to all food establishments and should at least be considered by every practitioner of food defense. They include physical security measures like fences and door locks. They also include behavioral or procedural measures like developing employee awareness and auditing your performance. Many organizations have taken specific steps to deter intentional contamination such as tamper-evident seals on

packaging. While sophisticated physical measures can enhance your food defense program, overreliance on them can present its own danger. Even the most sophisticated locks have little value if employees intentionally jam them.

Besides being classified as physical and behavioral, basic mitigation measures are often classified in additional ways. These are artificial classifications used for administrative purposes. They organize similar topics together and help assure that a broad range of mitigation measures are included. The US FDA uses these classifications (US FDA, 2007):

● Management (systems)

● Human element – staff

● Human element – public

● Facility

● Operations

An alternative organization system (Periscope Consulting, 2010–2012) uses: ● Outside (perimeter) security ● Inside security ● Logistics, production, and storage security ● Management systems It is beyond the scope of this article to provide an exhaustive list of potential mitigation measures. The food defense practitioner is encouraged to research sample plans, assessment checklists and guidance documents, including the FDA guidance document referenced

above. The World Health Organization (WHO) also provides a helpful checklist (WHO, 2008). Below, however, are a few examples of basic mitigation measures in each classification (Periscope Consulting, 2012).

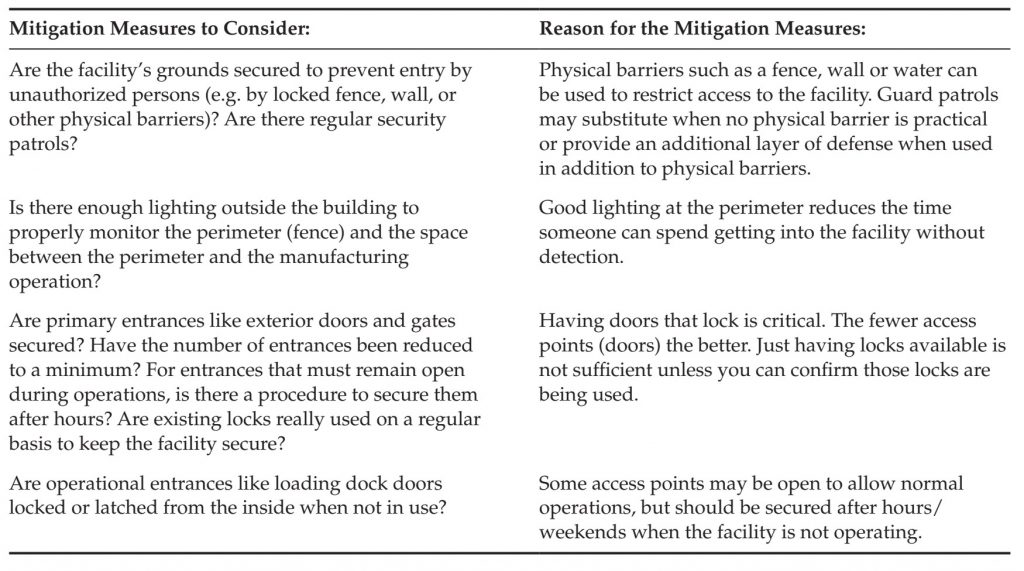

Outside (Perimeter) Security

Outside (perimeter) security has to do with the walls, fences, doors, etc. that keep an attacker out of your operation. These are most effective against outsiders, but provide little protection from employees and other insiders.

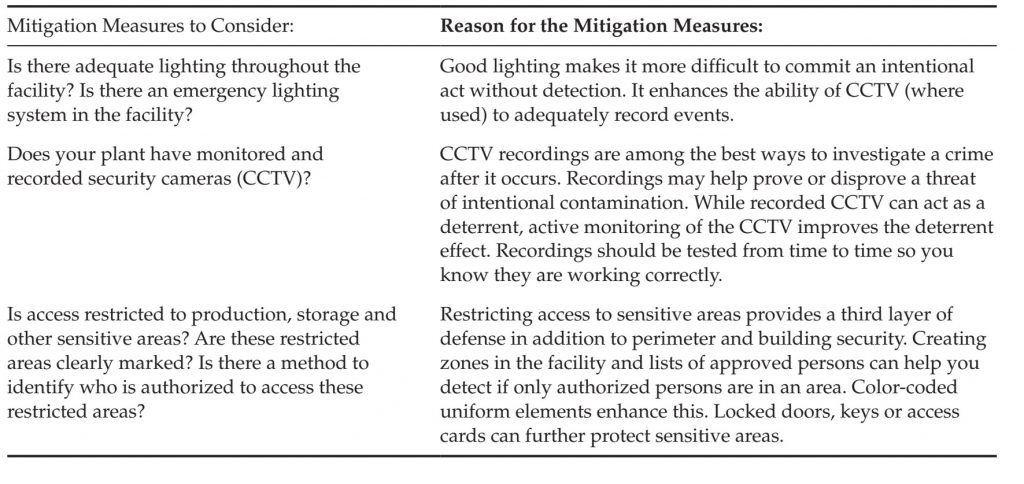

There are two important considerations with perimeter security. The first consideration is the concept of “layered” security. You will see this in military history: an inner and outer city wall, for example. This means that not only is each perimeter barrier impenetrable, but that collectively they slow down an attacker, making it more likely that they are detected. The second consideration is that you must ensure the barriers remain effective. If the fence is not inspected for damage, and underbrush is not cut away from the wall, or doors are not closed and locked, your defenses will not be effective. Table 2 shows some sample mitigations to consider. Inside Security Inside security has to do with measures in place once an attacker has got inside, including lighting, cameras and internal access restrictions (zoning). These measures are effective against outsiders, but also provide protection from employees and other insiders. There are two important considerations with inside security. The first consideration is the concept of detection. What can you do to make it easier to detect or recognize an attacker? Ideally this would be prior to an intentional contamination. But even detecting the contamination event has benefits, since you would not knowingly ship a contaminated product and thus would reduce the health impact. The second consideration is to create additional layers of security, like the layers described in outside security. Zoning the facility, authorizing access only to individual work areas and putting in additional access controls (walled areas with locked doors) all reduce the risk of contamination. These measures do not prevent all people from accessing sensitive areas.

Table 3 shows some sample mitigations to consider. Note: Closed circuit television (CCTV) is a popular security measure in many larger facilities. You should understand that cameras are primarily forensic in nature – providing information after the fact to prove what happened and capture the perpetrator. You must actively monitor any cameras and respond to unusual activities for them to be effective.

TABLE 2 Justifications for Exterior Defense

TABLE 3 Justifications for Interior Defense

Logistics, Production and Storage Security

Logistics, production and storage security is concerned with measures in place with materials stored in your facility as well as moving materials into and out of your facility. These measures are effective against any attacker and also help to extend protection up and down the food supply.

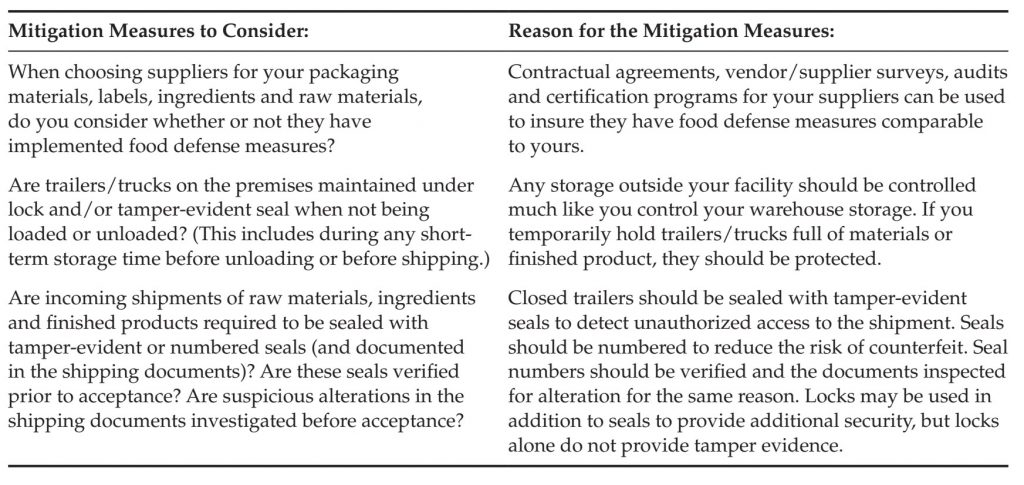

TABLE 4 Justifications for Logistics, Production and Storage Security

There are two important considerations with logistics, production and storage security. The first consideration is the concept of “farm to fork.” Because a contamination can occur anywhere in the supply chain, it is important to guard the entire supply chain. While you cannot directly control your suppliers, you can use your contractual agreements and supplier audits to help ensure that their food defense measures are comparable to your own. The second consideration is the critical importance of ingredients. If key ingredients are contaminated on your site or at your supplier, you will inadvertently, deliberately and effectively mix those contaminated ingredients into large batches of food that result in many consumer portions affecting the health of many people. This is why extra scrutiny of suppliers, inspection and testing of incoming ingredients, and protected storage of ingredients becomes so important.

Table 4 shows some sample mitigations to consider.

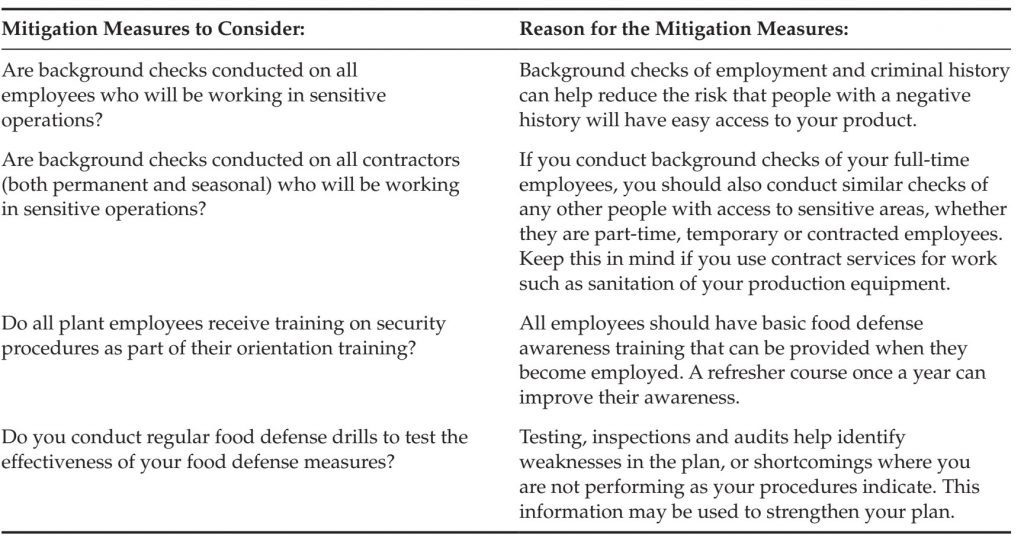

Management Systems

Management systems are concerned with the policies, procedures and training you put in place to create and maintain a robust food defense program. These systems knit your program together into a cohesive whole and perpetuate the program over time. There are two important considerations with management systems. The first is that your greatest risk is the people on your site. Careful selection and monitoring of all employees, contractors and temporary employees is important. Training and awareness for all employees is equally important – to promote vigilance and the reporting of unusual circumstances. The second consideration is the importance of monitoring the program itself. Without surveys, inspections or audits, it is easy to overlook the measures you promised to implement. Without periodic review and update, your program will not improve as new best practices are established. Table 5 shows some sample mitigations to consider.

TABLE 5 Justifications for Management Systems

Targeted Mitigation Measures

In order to target mitigation measures at specific vulnerabilities, a vulnerability assessment should be completed. (See the section above on vulnerability assessments.) Based on those vulnerabilities (e.g., product access in transportation, etc.), additional targeted mitigation measures (e.g., locks and seals, etc.) can be added to your food defense plan. Because the vulnerability assessment looks at unique characteristics of your process, the targeted mitigation measures are often specific and process related. The mitigations you choose will usually be related to the reason that location was deemed more vulnerable. For example, a blending operation is especially vulnerable because the blend tank is completely uncovered; therefore you may decide that a good mitigation measure is to add a lid. But if that measure is not practical, you could reduce the vulnerability in other ways, such as adding additional video recording or supervision of that location. Creating zones within your facility can have special importance for the sensitive areas highlighted by your vulnerability assessment. In the case of the vulnerable blend tank just mentioned, you can install additional access controls to the specific area and designate that area only for your most trusted employees to work in. If only your most trusted employees have access to your most sensitive work areas, you are well protected. If you want to further reduce your risk, you can consider a “buddy system” where no single employee is permitted in the area alone, as well as video recording those areas. These measures can help further reduce your risk in this special case. Mitigation lists and databases are worth considerating. The CARVER + Shock software previously mentioned displays some sample mitigations on its results screen. The self-assessment checklists previously mentioned can be scoured for suggestions; they are available by searching online. There are also mitigation strategies databases from the US FDA and the US DA available online. These databases let you look up sample mitigation strategies based on your selection of processing operation.

[ BRSM Certification is accredited for QMS ISO 9001, EMS ISO 14001, OSHMS ISO 45001, FSMS ISO 22000 and QMSMDD ISO 13485 and … ]

Mitigation Databases

● US FDA: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/fooddefensemitigationstrategies/Card.cfm?card=55

● US DA: http://www.fsis.usda.gov/Food_Defense_&_Emergency_Response/Risk_ Mitigation_Tool/index.asp

(Alternatively these databases can be accessed by visiting www.fda.gov or www.usda. gov and searching for “food defense mitigation.”)

Regulatory Requirements

There are few government regulations dealing with food defense. Much of what is published is in the form of guidance documents recommending best practices, rather than mandatory requirements. If you operate in or export to the United States, you should familiarize yourself with the BioTerrorism Act (BT Act) and the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). The BT Act requires the registration of companies supplying to and an advance notification of shipments prior to their arrival in the USA. FSMA requires the FDA to address intentional contamination; future regulations to support this law will likely require food defense plans and a consideration of mitigation measures similar to those outlined in this article. In China, the Certification and Accreditation Administration (CNCA) established under the Administration for Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine (AQSIQ) has put forth guidance and regulation requiring food defense plans for exporting companies. The UK and Germany have robust food defense initiatives. Canada has its own study of vulnerability assessment methods. This is by no means an exhaustive list, but an indication of the global progress of food defense initiatives. You should inquire about the food defense requirements in your own country. This is an area that will probably see a great deal of development in the next few years.

HOW TO MANAGE THE CASE

Case studies and table-top exercises can reinforce your knowledge and allow you to practice your skills. There are excellent case studies and exercises available at no cost. The US FDA has created a set of five exercises: Food Related Emergency Exercise Bundle (FREE-B). They include scenarios based on both intentional and unintentional contamination events. While these are targeted towards agency use, they include the provision for the private sector to participate, and they may be instructive on their own. They are freely available at www.fda.gov/fooddefense (search for FREE-B.) The following case studies focus on recall and were based on food safety incidents. Recall

is also important to food defense, and two of the three studies have a section entitled “What if Contamination were Intentional?”

FOOD RECALL CASE STUDIES

(http://foodindustrycenter.umn.edu/EducationalResources/index.htm)

1. Westland/Hallmark 2008 Beef Recall: A Case Study by the Food Industry Center (.pdf) Seltzer, J., Rush, J. and Kinsey, J. The Food Industry Center, University of Minnesota. January 2010.

2. Natural Selection 2006 E. coli Recall of Fresh Spinach: A Case Study by the Food Industry Center (.pdf)

Seltzer, J., Rush, J. and Kinsey, J. The Food Industry Center, University of Minnesota. October 2009. Natural Selection Case Study Learning Module

Problem Set Instructions (.pdf)

Problem Set Instructor’s Guide (.pdf)

Problem Set Data (.xls)

3. Castleberry’s 2007 Botulism Recall: A Case Study by the Food Industry Center (.pdf) Seltzer, J., Rush, J. and Kinsey, J. The Food Industry Center, University of Minnesota. August 2008.

[ BRSM Certification is accredited for QMS ISO 9001, EMS ISO 14001, OSHMS ISO 45001, FSMS ISO 22000 and QMSMDD ISO 13485 and … ]

References

– Air Force Instruction 10-245. Air Education and Training Command, Supplement 1, 15 May 2005. Air Force

Antiterrorism Standards. Attachment 14.

– Cavallaro, E., Date, K., Medus, C., Meyer, S., Miller, B., Kim, C., et al., 2011. Salmonella Typhimurium infections

associated with peanut products. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 601–610.

– CDC, 2006. Ongoing Multistate Outbreak of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 Infections Associated with

Consumption of Fresh Spinach – United States, September 2006. MMWR Dispatch September 26, 2006/55

(Dispatch); 1–2.

– Detlefsen, C., 2005. Dairy industry vigilant in addressing food security. Cheese Market News 25(22), 1.

-Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 1998. Food quality and safety systems. A training manual on food hygiene and the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) System (Section 3).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2010. Global hunger declining, but still unacceptably

high. Economic and Social Development Department, September 2010.

– Food and Agriculture Sector-Specific Plan, 2010. An Annex to the National Infrastructure Protection Plan. <http://

www.dhs.gov/files/programs/gc_1179866197607.shtm>.

– Food Safety Magazine online article, October/November 2010. Product Tracing in Food Systems: Legislation versus Reality, by Jennifer Cleveland McEntire, PhD.

– Food Safety Magazine, December 2011/January 2012, The Food Safety Challenge of the Global Food Supply, Gary Ades, PhD, Craig W. Henry, PhD and Faye Feldstein.

– Hennessey, M., 2010. Risk Evaluation Tools and Food Defense. North Central Cheese Industry Conference, 13

October 2010.

– Hoffman, J., Kennedy, S.P., 2007. International cooperation to defend the food supply chain: nations are talking;

next step – action. Vanderbilt. J. Trans. Law. 40, 1169–1178.

-Kennedy, S.P., Busta, F.F., 2007. Biosecurity: food protection and defense. Article 5. In: Doyle, M.P., Beuchat, L.R.-(Eds.), Food Microbiology: Fundamentals and Frontiers, third ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC, pp. 87–102.

– Khan, A.S., Swerdlow, D.L., Juranek, D.D., 2001. Precautions against biological and chemical terrorism directed at food and water supplies. Public Health Rep. 116, 3–14.

– National Standard of the People’s Republic of China, GB/T-27320 – 2010, Food Defense Plan and Guidelines for its Application – Food Processing Establishments.

– Newkirk, R., 2010. Risk & Vulnerability Assessment Methodology for Food Systems. <http://www.orau.gov/

dhssummit/2010/presentations/March10/Panel06/newkirk_ryan.pdf>.

– Periscope Consulting, 2010–2012. Asian Pacific Economic Cooperative, Food Defense Workshops, Food Defense

Plan Builder Tool, copyright 2010, 2011, 2012.

– Periscope Consulting, 2012. The excerpts of mitigation tables are used with permission from Periscope Consulting,

taken from their Food Defense Plan Builder Tool, copyright 2012.

– The New York Times, 2011. Melamine – China tainted baby formula scandal. <http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/subjects/m/melamine/index.html>, updated 4 March 2011.

Torok, T.J., Tauxe, R.V., Wise, R.P., Livengood, J.R., Sokolow, R., Mauvais, S., 1997. A large community outbreak of salmonellosis caused by intentional contamination of restaurant salad bars. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 278 (5), 389–395.

– Tumin, T., 2009. Visualizing food safety: seeing the linkages in a networked world. A fire under embers. <http://

blogs.law.harvard.edu/fireunderembers/> (accessed 21.10.11.).

– United States Food and Drug Administration, 2007 Guidance for Industry: Food Producers, Processors, and

Transporters: Food Security Preventive Measures Guidance. March 2003; revised October 2007.

– Watts, J., 2004. Chinese baby milk blamed for 50 deaths. Guardian 20. World Health Organization, 2008. Terrorist Threats to Food – Guidelines for Establishing and Strengthening Prevention and Response Systems (revised version – May 2008).